Of course, it may be different this time but let’s get some perspective.

Many sophisticated investors know that equity valuations are high. But, just how high are they and what does that really mean to investors buying stocks right now?

First, let’s imagine we are interested in buying shares in a corporation. We know what the earnings of the corporation are, so take that figure and divide it by the number of outstanding shares. That gives us the earnings per share. Let’s say it’s $2 per share. Next, determine at what the stock is trading for. Let’s pick $34. Simply divide the cost of the stock, $34, by the $2 earnings per share, to calculate the stock is trading at a “multiple” of 17 times earnings, or a P/E (Price-to Earnings Ratio) of 17.

I know that the majority of you are sophisticated investors and this is elementary, but I think it will get more interesting.

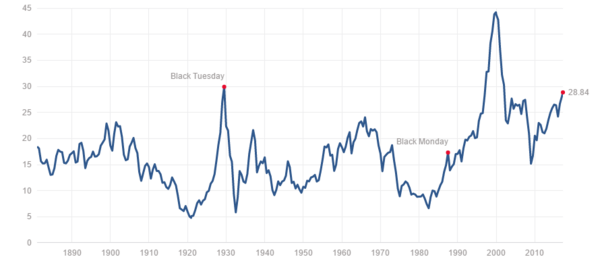

Let’s consider the benchmark S&P 500 for a moment and the median figure or “fair market value” that divides the stock earnings universe into two, companies with a P/E higher and half with a lower P/E. Armed with this information we can evaluate all stocks traded over the last 53 years to determine what has been the median P/E Ratio. Today, that valuation is 17 times earnings. This is a simple metric to examine if your company or the stock index is expensive or cheap relative to the historic fair market value. Investors that use this methodology are known as “value investors”. Warren Buffet, Peter Lynch and John Templeton are a famous value investors. They would tell you that purchasing stocks when valuations are higher than the “fair market value” lead to lower returns over the long run and is far riskier. History shows they are correct.

From 1926 through 2014 the median annualized return in the subsequent 10 years following a purchase at the “Fair market value” was nearly 10%. However, stocks when bought in the lowest 20% of valuation appreciated nearly 16%. Stocks purchased in the highest 20% valuation only appreciated a little over 4%. That forward return number goes down considerably if we are in the top 10% or 5%, where we are today, at 24 times earnings. (Source: Ned Davis Research)

To make matters worse, not only are returns lowest at the high end of valuations, but risk is highest. Since 1940, stocks purchased at today’s valuations, should expect a drawdown in the next three years of -18% on average and worst case -51% if the economy experiences a recession. (Source: GMO, Hussman Funds)

So, am I recommending that everyone sell all their stocks? In a word—NO. Why not? Because we are in a serious bull market that is up over 50% in the last three years without any increase in earnings. Bull markets since 1947 have typically gone out with a bang, as investors rushed in, convinced that “this time is once again truly different.” While there have been many new all-time equity highs, the market has not really seen that big final sell-off top.

What I am saying is, taking new positions in the stock market should be done defensively rather than aggressively, and an allocation to alternative investments, with a low correlation to stocks (think managed futures), makes sense right now.

Tom Reavis

President

Worldwide Capital Strategies

The content of this article is based upon the research and opinions of Tom Reavis.